Modelling the reintroduction of the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja L. 1758) in southern Costa Rica

The harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) is one of the most iconic apex predators in the Neotropics, primarily inhabiting the Amazon basin and parts of Central America. It plays an important role in maintaining the balance of tropical forest ecosystems. In Costa Rica, however, populations have become highly fragmented, and the species is now considered locally extinct in the south. The last confirmed sighting in that region was more than 20 years ago. Osa Conservation is preparing a reintroduction in the Osa Peninsula, an area known for its ecological richness and extensive forest cover. Successfully restoring a large raptor like the harpy eagle requires careful modelling, long-term planning, and a detailed understanding of how individuals might disperse, establish territories, and survive over time.

This project was originally part of a university course and developed in collaboration with Pablo Aycart Lazo and Markus Milchram. Since then, I have fully implemented and substantially expanded it, exploring different reintroduction strategies.

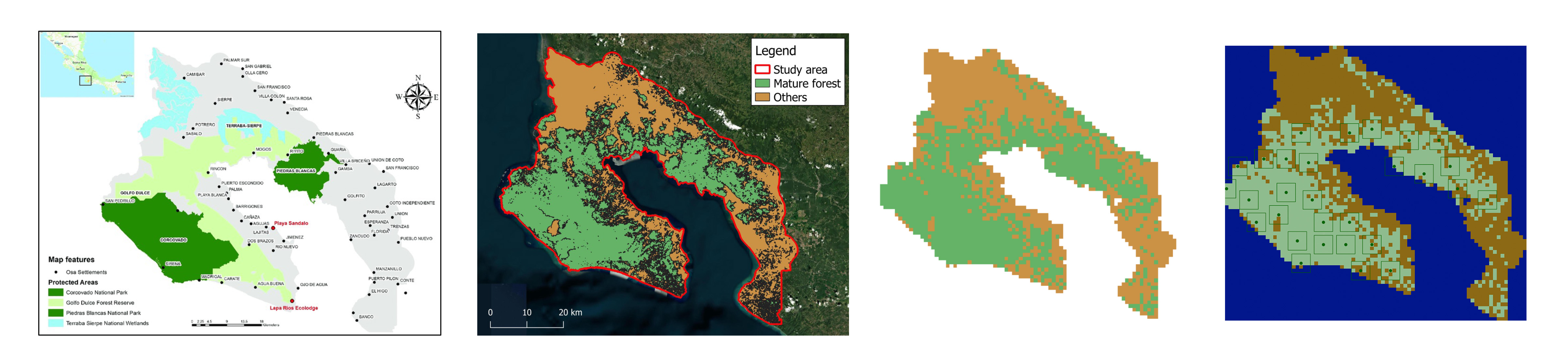

Study Area

Spanning 2,835 km², the Osa Peninsula is home to 2.5% of the world’s living species, including the famous Corcovado and Piedras Blancas National Parks. The harpy eagle, as a predator of arboreal mammals, plays an important role in shaping rainforest ecosystems, influencing nutrient distribution, and maintaining ecological balance.

Building the landscape, the model starts by generating a raster grid where each cell represents either suitable habitat (forest) or unsuitable land. Territories are precomputed by selecting random locations that meet habitat criteria while ensuring a minimum distance between them. A sea buffer is added around the landscape to prevent unrealistic dispersal beyond the peninsula.

Research Questions

To better understand the feasibility and potential outcomes of a harpy eagle reintroduction, we explored the following:

How many pairs should be released to ensure population establishment?

How long would it take for the species to colonize the peninsula under different scenarios?

How does release location (random vs. protected areas) affect dispersal success?

Scenarios

Our individual-based model simulated different reintroduction scenarios:

Number of released pairs (1, 3, or 5)

Release locations (random vs. protected area)

Mortality function (exponential vs. constant)

Carrying capacity (100, 200 or 400 individuals) in the case of exponential mortality function

The model ran 10 simulations per scenario, tracking random movement, territory acquisition, breeding success, and mortality over a timespan of 167 years (2000 time steps, 1 month per step). Juveniles left the nest after two years, reaching maturity at 2.5 years old, while adults followed random-walk movement based on habitat suitability (forested vs. non-forested areas).

Mortality

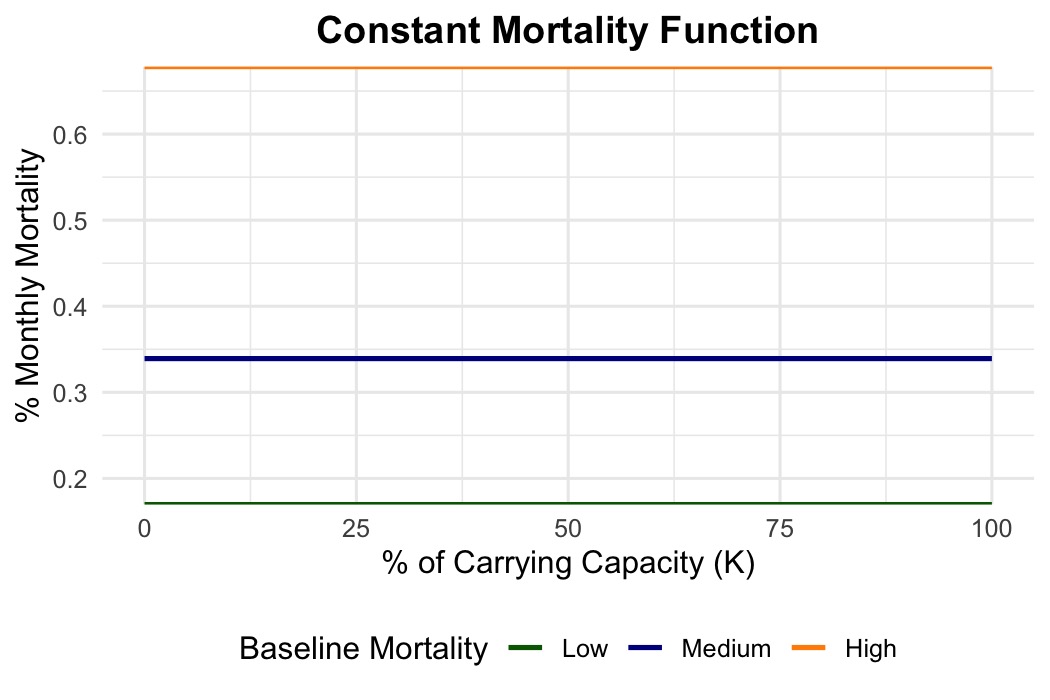

Mortality was modeled either as constant or density-dependent.

Under the constant scenarios, individuals experienced a fixed monthly death rate independent of population density. We began with baseline monthly mortality values representing minimal background mortality:

Low baseline: 0.0008 per month (approx. 99% annual survival)

Medium baseline: 0.0016 per month (approx. 98% annual survival)

High baseline: 0.0032 per month (approx. 96% annual survival)

These values were derived from plausible survival rates reported in the literature, particularly for juvenile harpy eagles, which tend to face higher mortality than adults. However, because these baseline values led to unrealistically high survival across the full lifespan, we applied a uniform multiplier of 2.12, resulting in more realistic annual mortality cutoffs (~2%, 4%, and 8%).

| Scenario | Baseline Monthly Mortality | Adjusted Monthly Mortality | Annual Mortality | Expected Lifespan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 0.0008 | 0.001696 | ~2% | ~49 years |

| Medium | 0.0016 | 0.003392 | ~4% | ~25 years |

| High | 0.0032 | 0.006784 | ~8% | ~12 years |

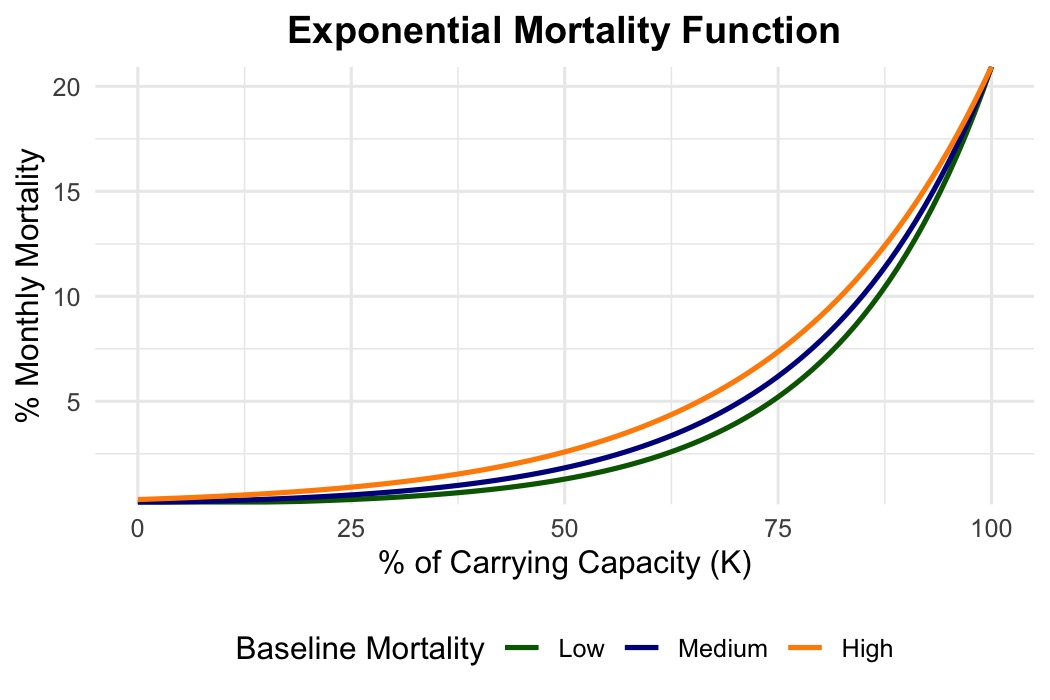

This approach assumes mortality is constant for all individuals, regardless of population density. In an effort to make the model more realistic, we can use an exponential mortality function to simulate density-dependent survival. This function starts at the same baseline values used above, but increases smoothly with population size, reaching a maximum monthly mortality of 0.2094 at the carrying capacity (K).

This upper bound corresponds to 97.5% annual mortality under extreme crowding, and was chosen to reflect a strong ecological limit on population size. The value was guided by statistical reasoning: according to the Central Limit Theorem, population sizes across many simulations approximate a normal distribution, and the two sigma rule tells us that around 95% of values fall within two standard deviations of the mean.

Since this range is symmetrical, only 2.5% of population sizes are expected to exceed two standard deviations above the mean. By placing the carrying capacity at this upper 2.5% threshold and assigning it a very high mortality rate, the model ensures that population growth is only strongly limited under rare, overcrowded conditions, while remaining lenient under typical densities.

Simulating Harpy Eagle Reintroduction

For individual movement and behavior, each eagle in the simulation follows a random walk model but with constraints based on habitat suitability. Eagles move 2 km per month in forests and 4 km per month in open areas. Individuals search for a mate once they reach maturity at 25 years and occupy an available territory of 25 km². If one member of a pair dies, the surviving partner may return to random movement.

Breeding and population growth dynamics ensure that once paired, eagles remain territorial, producing one juvenile every two years. Juveniles stay in the nest for two years before dispersing. Breeding success is limited by the number of available territories rather than the carrying capacity alone.

Mortality and survival functions are included in the model with two types of mortality. Linear mortality increases gradually with population size, while exponential mortality rises sharply as the population nears carrying capacity, set at either 100 or 200 individuals, simulating density dependence.

Implementation

Simulating the harpy eagle reintroduction requires careful thought to handle the scale of movement, territory assignment, and population dynamics. A naïve approach, where every eagle evaluates its movement options, searches for a mate, and checks for available territories in real time, would quickly become computationally infeasible.

One of the biggest inefficiencies in the simulations comes from recalculating the same values repeatedly. Rather than dynamically determining which locations an eagle can move to at every time step, the model precomputes movement options for every possible location in the landscape. This means that when an eagle needs to move, it simply looks up precomputed options rather than recalculating them from scratch. The same principle applies to territories, rather than scanning the entire landscape to find available nesting sites, the model keeps an up-to-date list of what is occupied and what is available. This dramatically reduced our computation time.

Many of our operations, such as calculating movement possibilities or assigning territories, can be done simultaneously rather than sequentially. By distributing these tasks across multiple CPU cores, the model speeds up operations that would otherwise slow down the simulation. Instead of iterating over every eagle one by one, groups of individuals are processed in parallel per time step, reducing the bottleneck of handling large populations.

Finding mates in a simulation is a challenge. Instead of iterating over every possible pair (which would be computationally expensive), the model:

Filters for mature males and females separately.

Iterates through available males and checks if they are in proximity to available females.

Checks available territories that both individuals can access before confirming a pair.

This avoids an exhaustive \(\mathcal{O}(n^2)\) complexity for pairwise comparisons.

Instead of dynamically expanding lists or recalculating movement at every step, the model preallocates space for individuals, their movement history, and population statistics. We aimed to keep the simulation realistic without adding unnecessary complexity. This led to the choice of fixing territories in advance rather than assigning them dynamically. Density-dependent mortality was left out to avoid slowdowns. Similarly, once a pair occupies a territory, they remain there until one of them dies.